Review: The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo by Taylor Jenkins Reid

Just as Evelyn’s seven husbands were a distraction from the real story, consider this review a decoy—it’s really about me.

I borrowed The Seven Husbands of Evelyn Hugo from my girl Lucy (shoutout to Lucy if you’re reading this) the second-to-last time I was in Michigan. That would’ve been March. The book made its way into my bag, then my bookshelf, then my nightstand, and then right back into my suitcase this past week when I returned to town.

I finally cracked it open over a month after initially receiving it and have now finished this book a week later and ten minutes prior to writing this piece. I know, I know, I’m so very late, especially as it seems this book was published way back in 2017.

Honestly, there was a time I saw Evelyn and her seven husbands everywhere—BookTok, Instagram, the works—and each time I scrolled right past it. I assumed it wasn’t my genre. Why? Well, because when it comes to fiction, I’m an unapologetic romance girl. Give me YA love triangles, historical heartbreak, second-chance contemporary stories, even fantasy—so long as love is at the center. But I don’t do gritty. The world is heavy enough. So I made a judgment, an assumption, really.

I was absolutely convinced this book was about a woman who married seven men... and killed them. Like, Evelyn Hugo: seductive black widow. I saw the cover and pictured blood-red lipstick, silk gloves, and champagne laced with cyanide. And while that book might’ve been compelling in its own right, I’d already decided I wasn’t in the mood to live in that kind of darkness. So I skipped it. Assumed it wasn’t for me.

But of course, what do they say about assumptions? They make an ass out of ‘u’ and ‘me.’ (And in this case, mostly me.) Turns out, I’m still struggling to learn the age-old kindergarten library homage, ‘don’t judge a book by its cover.’

This book is less about husbands and more about love—the kind we fight for, the kind we sacrifice, the kind we regret. It’s about identity, ambition, secrets, storytelling, and survival. And maybe most of all, it’s about how easily we believe the stories handed to us: the ones other people craft and package and sell, the ones we tell about ourselves, just to get through, the ones we tell other people because we are so concerned with controlling the narrative. And it’s that part—the part about performance, and perception, and the cost of trying to be palatable—that stayed with me after I turned the last page.

So yes, I’m going to talk about the book. But I’m also going to talk about me. Because this is Girlhood by Sarah, and I don’t know how to talk about anything I read without telling you what it revealed in me at the same time.

DEALING WITH THE BINARY

Both Monique—the book’s semi-narrator, a journalist tapped to write Evelyn Hugo’s posthumous memoir—and Evelyn herself wrestle with the impossibility of binaries, particularly as they relate to identity. For Monique, this shows up in her Black biraciality: never quite white enough, never quite Black enough, constantly moving through the world, unsure where she’s allowed to land. She’s on the brink of divorce, still grieving a father she lost too early, and underneath it all, there’s this quiet ache for understanding—for someone to see her, whole.

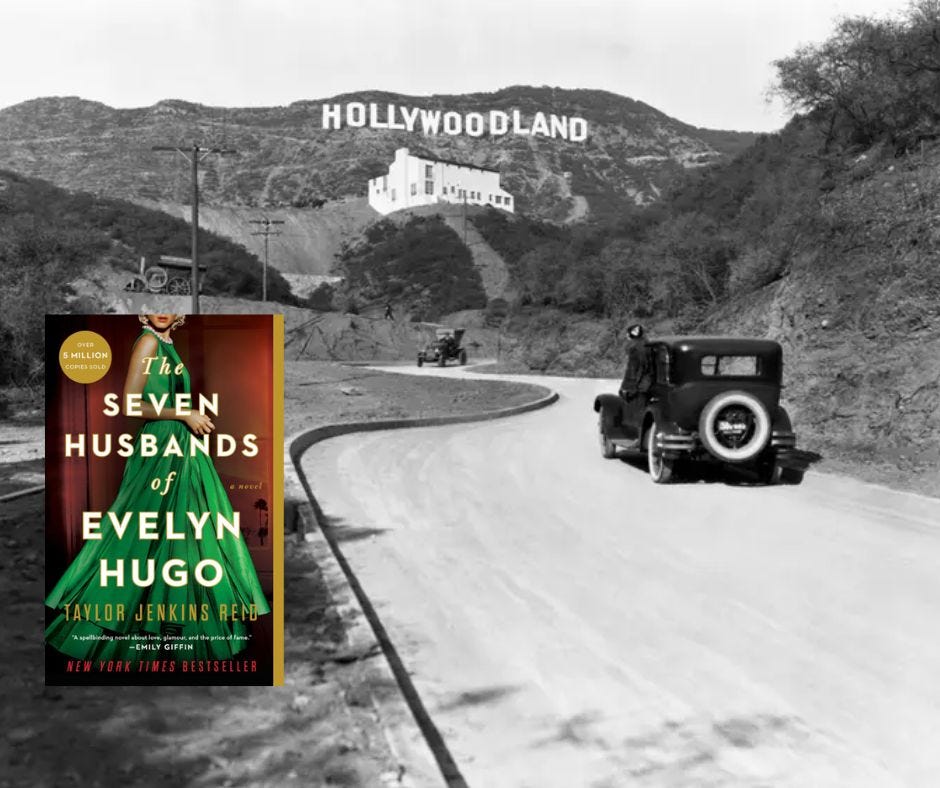

Evelyn, on the other hand, sidesteps that tension entirely (or so it seems). Though fully Cuban, she makes a deliberate choice early in her career to abandon any markers of that identity. She stops speaking Spanish, changes her last name, and attributes her olive skin to some vague Sicilian ancestry. She does what she must to survive Hollywood in the 1950s and 60s, and that means becoming someone America can desire, not someone it would other. And yet, the act of disappearing oneself for acceptance isn’t really an escape at all—it’s a performance.

It’s the same fractured identity W.E.B. Du Bois names in The Souls of Black Folk, what he calls “double consciousness”: the twoness of seeing yourself through your own eyes and through the distorted gaze of a society that insists you be either/or. Edward Baugh expands this even further, tying that twoness to the diasporic condition at large—a kind of existential split that defines how so many of us move through the world. Evelyn may reject her Cuban-ness, and Monique may still be searching for her place, but both are shaped by this unrelenting tension between how they see themselves and how the world insists on seeing them.

This tension—the ache to be seen as whole, not in pieces—isn’t foreign to me. I’ve known it intimately. The world has a way of demanding that you pick a side, of trying to carve you up and make your fragments tell the entire story. But what if the story is both/and? My own journey of finding home (word to my play) has never been neat or linear. Nigerian and American, foreign and native, familiar and estranged. I spent my earliest years pledging allegiance to a flag I would eventually leave behind, only to return to it years later as a stranger. Spending my teenage years in Mozambique, the continent of my forefathers, but not the country of my blood. A place that gave me memories, language, rhythm—but no true roots. Returning to the U.S. feeling somehow less Nigerian and less American, with nothing to anchor me but the twin truths of being Black and being a woman. I’ve made the choice, over and over again, to reject the false comfort of binaries—African or African American, foreign or native—and instead live in the in-between, the hyphen, the stretch of space where questions live. I’m still trying to figure out how to love a country that chews its people up and spits them out onto streets, into prisons, into poverty. I still don’t know if love is even required. Can you hate a nation and still hold deep, aching love for its people? What does it mean to fight for a place that will always call you foreign, not because of your twelve-letter last name, but because of the skin you live in?

And really, this dilemma of the binary isn’t just mine. It isn’t just Monique’s or Evelyn’s either. It’s everywhere—woven into the ways we police bodies and guard borders, categorize people as good or bad, legal or illegal, deserving or disposable. It’s in how we handle race and sexuality, and belonging. Even Evelyn’s great love, the person she cherished most, struggled under the weight of binary expectations: to be one thing or another. This book, in all its glossy Old Hollywood glamor, kept whispering beneath the surface: we are not either/or. We are everything, all at once. And the tragedy is how much of ourselves we are taught to deny just to be allowed to exist.

LOVE, LIES, AND PERFORMANCE

So we perform. Or we pretend. We give the world a cleaner, more palatable story to hold onto. We round out our edges, smooth out our contradictions. We let go of some, or half, or even most of ourselves—not to deceive necessarily, but to avoid raising questions. To prevent the awkward conversation, the uncomfortable pause. We trade the messiness of truth for the safety of performance. Evelyn Hugo spent her whole life performing—beautifully, strategically, heartbreakingly. And perhaps Monique, in her own quiet way, did the same within her marriage. They both put on a show, let others fall in love with the script, all the while never informing their stage partner that it was all an act. At Evelyn’s best, it was calculated manipulation. At Monique’s worst, it was self-protection laced with low self-worth. But either way, the result was the same: when we force ourselves into a binary, we force the world to understand us that way too.

And when we hide, we limit. We limit the love we’re able to receive because deep down, we know people are loving the performance, not the person. (Evelyn knew this well—her marriage to Max Girard was nothing if not a study in hollow admiration.) We also limit the love we’re able to give, because how can you offer your whole heart when it’s hidden under layers of disguise? The depth of love Monique’s father had for her—his care, his sacrifice—could only be truly understood once the full truth of his identity was revealed. Only then could she comprehend the magnitude of what he’d risked. Only then could she receive that love fully. And Evelyn? She lost years—decades—with the person she loved most in the world because neither of them could choose exposure over erasure. Because neither of them could afford to love out loud.

Which brings me to me. I currently have the privilege of being in love. And what a quiet miracle that is. Because there are so few things in this life you can simply be. Most things require effort or explanation, fixing, or performing. But love—when it's real—asks only that you be. And yes, love is a two-way street (or so they say), but I think it’s more like three. The first is to love. The second is being loved in full truth, with all the lights on. And the third—the one we speak of the least—is the ability to love out loud. To let your love be seen by the world, unedited.

For much of our nation's history, that third street wasn’t available to everyone. Whether it was loving across racial lines or loving someone of the same sex, many were forced to hide their love in the shadows. Forced to carry their joy in silence. To perform. To pretend. To protect. Because to love openly could mean exile, imprisonment, or death. This reality is laced through Evelyn’s story and Harry’s too.

And even now, with so much progress behind us, I still find myself wrestling with that third street. I think about the man I love so deeply, who many of you know through my poems, my stories, my nickname-laced musings about “mister man.” And still, I catch myself performing. Still, I wonder if I’ve made loving out loud harder than it has to be. For Evelyn, that might’ve looked like holding hands in public. For Harry, it might’ve looked like grieving honestly, without needing to name it something else. For me, it might look like a real conversation with my father. Or providing my coworkers with a tad bit more insight into this long-distance love of mine. Or even just letting the world see the whole truth, past the poetry. It might mean letting my love be big enough to be misunderstood.

Because no, I don’t fear for my safety. I don’t fear exile or imprisonment. I fear assumptions. I fear the narratives others will create in my silence—the blanks they’ll fill in with their own biases. The stories I’ll never get to correct. But still, I wonder: if the cost of hiding is limitation, then what might be gained in the unveiling?

I think to love, to be loved, and to love out loud might be the most sacred trilogy there is. I think the more we love out loud, the more we widen the world’s imagination of who gets to love and be loved. I think the less we perform, the more we can rest. No longer waiting for applause, no longer anticipating critique. And I think the less we limit, the more we expand—the more room we make for a love that’s real, unflinching, and whole.

In this journey of becoming — this journey from girlhood to womanhood — I aim for more truth-telling, for more love-sharing, and less performance.

I'm so glad you posted about this book! I also picked it up late. I knew absolutely nothing about it other than people seemed to love it.

I saw how large it was and I was like, daunted by it. I actually chose to listen to the audiobook because I had a ton of driving to do and it was *AMAZING!* One of the best narrations of an audiobook I've ever heard. I highly recommend it! It's now one of my favorites. <3